Buffered VS Unbuffered channels in go

You’ve probably heard the phrase:

“Don’t communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.”

In Go, the primary tool for that communication is the channel. But just when you think you understand channels, you run in a make statement like this:

ch := make(chan int, 5) // What does the 5 do?

Versus this:

ch := make(chan int) // No number?

That single number is the defining difference between buffered and unbuffered channels and it fundamentally changes how the program behaves.

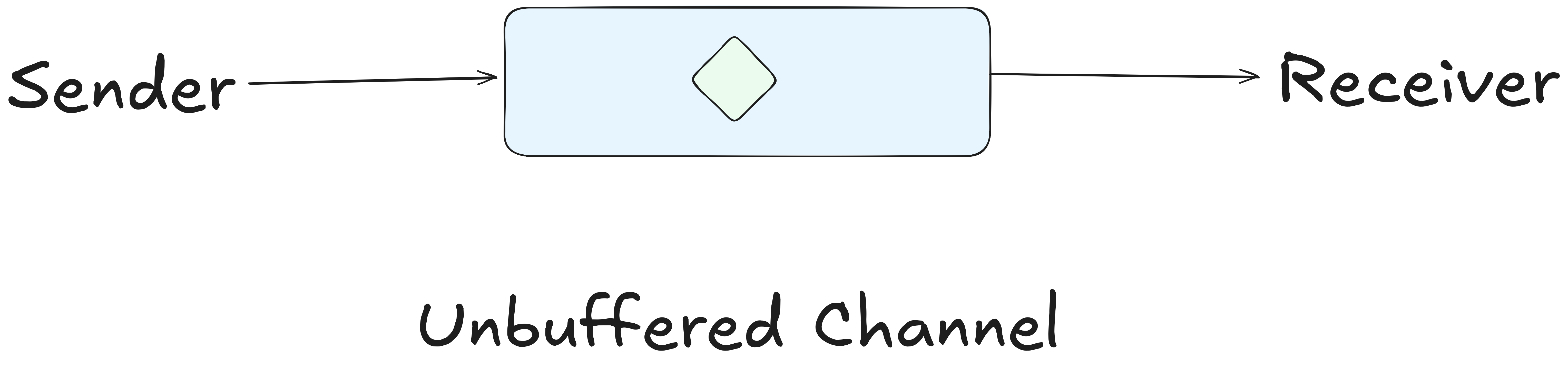

Unbuffered Channels (Synchronous Handshake):

An unbuffered channel has no capacity to hold data and it is the default channel type in go. Think of it like a direct hand-off. If you are passing a baton to a runner in a relay race, you cannot let go of the baton until the other runner has grabbed it.

-

Sending: The sender blocks (waits) until a receiver is ready to pull the data out.

-

Receiving: The receiver blocks (waits) until a sender is ready to put data in.

ch := make(chan string)

go func() {

ch <- "hello" // blocks until message is received

}()

msg := <-ch // unblocks sender

fmt.Println(msg)

Because both ends must be ready at the same time, unbuffered channels provide a synchronization guarantee. This means This means when a send completes, you know someone has received the value.

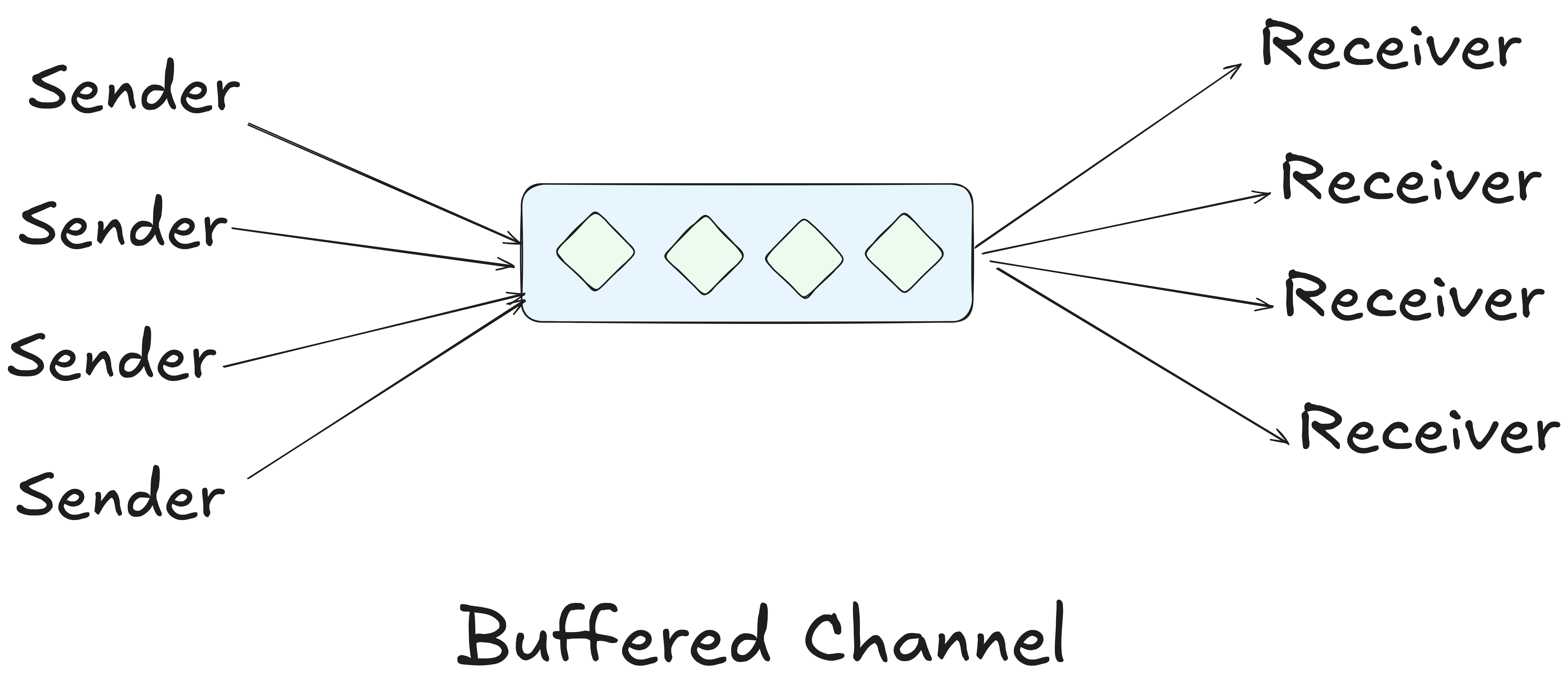

Buffered Channels: Asynchronous

A buffered channel has a fixed capacity and it can hold specific number of elements before it blocks. It internally maintains a FIFO queue.

Think of it like a PO Box. You can drop a letter in the PO Box and walk away immediately, even if the mail carrier hasn't arrived yet. You only have to wait if the PO Box is fully stuffed.

-

Sending: The sender only blocks if the buffer is full. Otherwise, it enqueues the value and moves on.

-

Receiving: The receiver only blocks if the buffer is empty.

func main() {

// Create a buffered channel with capacity for 4 strings

ch := make(chan string, 4)

ch <- "Message 1" // Doesn't block

ch <- "Message 2" // Doesn't block

ch <- "Message 3" // Doesn't block

ch <- "Message 4" // Doesn't block

// ch <- "Message 5" // This WOULD block because the buffer is full (4/4)

fmt.Println(<-ch) // Receives "Message 1"

fmt.Println(<-ch) // Receives "Message 2"

fmt.Println(<-ch) // Receives "Message 3"

fmt.Println(<-ch) // Receives "Message 4"

}

This channel decouples the sender from the receiver. One side can temporarily run faster than the other without immediately blocking. However, this comes with an important trade-off:

A successful send does not guarantee the value has been received, it only guarantees that it has been queued. Buffered channels sacrifice synchronization in exchange for flexibility and throughput.

When do you use which?

Use Unbuffered Channels When:

-

You need synchronization: You want to ensure step A happens before step B continues.

-

You need guaranteed delivery: You want to know for a fact that the data was processed before moving on.

-

You want simplicity: They are less complex to reason about regarding state.

Use Buffered Channels When:

-

Burst handling: You have a producer that sends data in bursts (spikes), and you want to prevent it from slowing down while the consumer catches up.

-

Performance tuning: You want to reduce the latency of "context switching" between goroutines by batching up a few tasks.

-

Limiting concurrency: You can use a buffered channel as a semaphore to limit how many goroutines run at once.

Rule of Thumb

Start with unbuffered channels and add buffering only when you need it.

Buffered channels are powerful but they can also hide slow consumers, delay backpressure, and make bugs even harder to figure out.